After wrapping up our time in Pond Inlet on the north shore of Baffin Island, we made a connection through Iqaluit and arrived at the Inuit village of Pangnirtung (aka Panniqtuuq), which is nestled deep within a fjord of southeastern Baffin Island.

Pangnirtung: “the place of the bull caribou”

Pangnirtung is located on the Cumberland Peninsula, northeast of Iqaluit. It means “The place of the bull caribou” in Inuktitut (ᐸᖕᓂᖅᑑᖅ). The large fjord where the village is in shares the same name and runs southwest-northeast: southwestward, it connects to Cumberland Sound; northeastward, it leads inland to Auyuittuq National Park.

I had read on Reddit that flight punctuality at Pangnirtung airport is consistently poor due to complex air currents within the fjord. However, we were lucky enough to have clear and calm weather so our landing was very smooth. Our flight departed Iqaluit at 8am and arrived right on time at 9am. We immediately headed to the hamlet office to collect the key for our accommodation. The village’s only other guesthouse – besides the expensive Inns North hotel – was fully booked, so we asked the hamlet office to help us arrange for a room in their employee dorm.

The hamlet office is right on the fjord’s edge, and with the addition of blue skies and white clouds, the view from there was absolutely stunning. It was high tide at the time, and no rocks were visible on the sea’s surface – we’ll touch on the tides again later, so I’ll save that story’s details for now.

The accommodation they arranged for us was in a two-story house. When we got there, we found out that the rooms upstairs were already occupied by two researchers studying Arctic char and an engineer from Quebec specializing in soil remediation – there was an oil spill near the fuel tanks and all contaminated soil needed to be shipped to Montreal for microbial oil removal, with the cleaned soil then being shipped back. The only room left for us was a rather dark one downstairs. Though the conditions were extremely basic and pricy, we made it work since it was only for one night. But if I were to come back, I wouldn’t stay there again to be honest.

Although the population of this village is similar to Pond Inlet (~1,500 people), we found it noticeably busier here: various trucks were driving back and forth, suggesting a fair amount of construction work was underway, which naturally means more workers visiting in town. We also saw tourists from time to time as the Akshayuk Pass in the national park is somewhat famous among the hard-core trekking and mountaineering community. Completing the full 100km/60mi Akshayuk Pass trek takes roughly a week of backpacking to traverse the entire national park via the valley.

We headed out to explore the village after dropping off our bags and resting briefly. The clouds had started to thicken by noon, and the tide had receded significantly. We asked some locals and learned that the tidal range in Pangnirtung is quite dramatic, comparable to that of the Bay of Fundy!

When we returned to look at the fjord later in the afternoon, the rocky seabed was completely exposed.

Just like Pond Inlet, Pangnirtung also has two main stores: Northern and Co-op. The only restaurant is a KFC inside the Northern store, but the KFC’s opening hours are quite unpredictable.

The village’s soul shines through the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts, a world-renowned institute of Inuit art. The exterior of the building is symbolically designed to mimic a connected shapes of a traditional Inuit tent and an igloo. It houses the Pangnirtung Tapestry Studio and a retail shop inside.

We saw a couple Inuit women chatting while weaving scarves and hats in the studio when we visited. The atmosphere was warm and cozy Their tapestries typically depict local life or mythological stories: one very large piece is actually displayed at the airport. They also made other knitwear such as the famous “Pang Hat” and various scarves.

The village is small. It only takes 15 minutes to walk from the hamlet office to the westernmost edge. The tide was still very low when we reached the far west. A large expanse of mudflats stretching toward the open sea was exposed. Many locals were out digging for mussels and clams with buckets, creating a wonderfully authentic scene of daily life.

Auyuittuq National Park

Before the tour

We had arranged a boat tour into the national park for the next day, but since we weren’t leaving until noon, we had some time in the morning to visit a couple of spots we’d missed:

The first was a fishing gear shop located east of the dock. The engineer staying in our residence told us that the shop’s freezer sold local fish, but it only opened in the morning. We checked it out and were delighted to find they sold pitsik (dried Arctic char)! This fish is similar to salmon, and once caught, the locals bone it, leave the skin on, score the meat into a lattice pattern, and then air-dry it outdoors to be eaten directly. This cured fish is high in protein and holds a significant place in the traditional Inuit country food, comparable to maktaaq (whale skin and blubber), caribou meat, and blueberries. We tried it with a little salt, and it was incredibly fresh.

The other place was the village museum, which is connected to the library. The museum is small but has a rich collection of exhibits, displaying fishing tools, traditional clothing, and many bone artifacts and specimens. The staff were very welcoming and eager to answer questions, patiently explaining a traditional game called inugaq to us.

The Inugaq game basically involves cleaning and drying various-sized seal bones, placing them in a small, opaque leather pouch, and then using a thin loop of string to “fish” them out. The bones successfully retrieved are then arranged to form a pattern of “a family and a dog inside an igloo.” The string is very fine and difficult to loop around the bones, and since many bones are required for the final pattern, it seems like a very challenging game. We asked the staff if the game was quite time-consuming, and she joked, “It was designed to be difficult, otherwise how would hunters pass the long polar night when they were out in their tents during the winter?”

It makes perfect sense! 😂

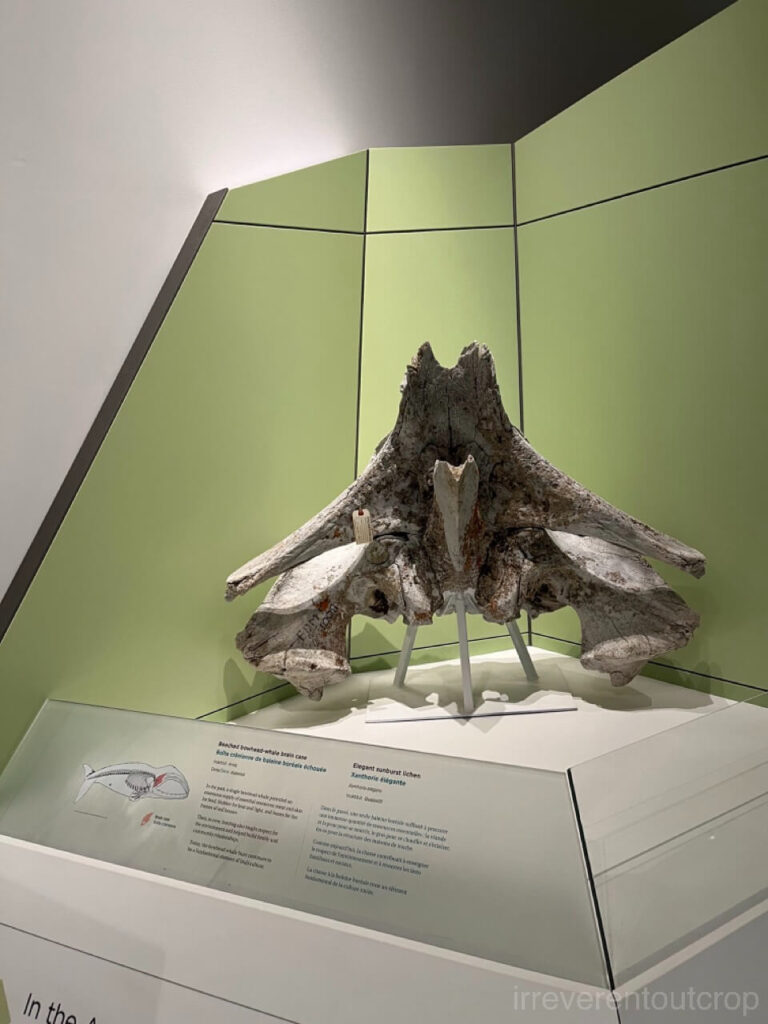

The Pangnirtung museum also houses a massive bowhead whale cranium, which is even larger than the one we later saw at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa!

As it approached our departure time, we started walking toward the dock.

Getting this boat tour to happen was actually quite an effort. Before arriving in Pangnirtung, I had been trying hard to find someone to take us into the national park for a day or half-day tour, but the three people recommended by the national park office were all unavailable. We realized we would have to wait until we landed in Pangnirtung to figure it out. Once here, the hamlet office staff helped us and brought us to the radio station and broadcast our names and contact phone number across the village to see if anyone was free to take us out.

“Everyone here owns a boat, so it doesn’t matter who takes you in anyway, right?” the hamlet staff member said.

Sure enough, about half an hour later, someone called to connect with us! He was a local Inuit truck driver.

A funny “side effect” of broadcasting our request was that the entire village knew we were looking for a boat. So while walking around the village, even though no children called me “Little Yao Ming” like they had in Pond Inlet, every so often a passerby would say hi and ask about our boat search: “You’re the one looking for a boat, right? Did you finally find one?” It’s pretty cute.

The weather was perfectly clear the first morning, so we initially planned to leave that same afternoon. But later our plan collapsed: our guide’s engine had a starting problem and then a torrential downpour began as he tried to borrow his uncle’s boat. We had no choice but to cancel and reschedule the tour for the following midday.

However, that rain – which was rain in the village – fell as snow higher up on the mountains. Looking into the fjord the next morning, we saw the mountains wore a fresh layer of white snow, instantly adding incredible depth and contrast.

Departure

Eventually we used our his uncle’s fishing boat, which was fully equipped with rifles and fishing gear. Our guide also brought his seven-year-old daughter along with him.

We passed the Kunguk Peninsula after about 20 minutes. The fjord gradually shifted its orientation from southwest-northeast to south-north, and the water was mostly calm under the cloudy sky. It only got bumpy at times when the boat made sharp turns at our guide’s driving speed of 60 km/h (40mi/h). His daughter stayed in the bow cabin playing on her phone the entire time, completely immune to motion sickness.

The fjord’s end soon appeared, a distant beach faintly visible. This allowed us to catch first sight of the towering cliffs nestled deep in the valley.

The end of the fjord terminates in a proglacial outwash beach, formed by glacial meltwater transporting and depositing inland till – a process known as glaciofluvial deposition. Adventurers crossing the Auyuittuq National Park typically disembark here and begin their week-long northward trek.

The village on the other side of the valley is called Qikiqtarjuaq. We asked our guide if he knew anyone there. “Yes,” he said, “but I had only visited Qikiqtarjuaq once.”

So, I asked him, “Did you hike across?”

He quickly waved his hand and said, “Oh, no, no, no… I’m not that crazy. I went in the winter when everything’s frozen. You can just ride a ski-doo straight across. It takes about 6-8 hours.”

“So locals here don’t usually hike through the valley?”

“Nah. Only the tourists do the hiking.”

Since we hadn’t secured the necessary permits from the national park office to go ashore, we simply spent some time relaxing where the water meets the land. Our guide provided a stove and coffee, allowing us to quietly enjoy the moment surrounded by the towering cliffs.

Latiao (spicy snack) and TikTok

The fjord surroundings were incredibly quiet, with hardly a bird in sight. Suddenly, music began playing from a phone in the bow cabin. I listened closely and recognized the song as Yu Yar’s “The past can only be remembered.” It’s an old Mandarin pop song from the 70s. Then a little girl’s voice, speaking in perfectly clear Mandarin, said, “Boss, two sticks of latiao (spicy strip snack).”

I was shocked and confused. Then I turned around and saw our guide’s daughter was still tucked away in the bow cabin on her phone. I crouched down, curious to see what she was watching, and found that she was scrolling through TikTok. The original latiao video was in Chinese but was subtitled in what looked like Malay or some other language, and the account that reposted it was in yet another language.

Deep in an uninhabited Arctic fjord, an Inuit girl on a fishing boat was using mobile data to watch a TikTok video in Chinese. Modern connectivity and technology reached far indeed!

While marveling at the strength of the cell signal, I asked our guide, “Does your daughter speak Chinese??” He laughed and replied, “That’s completely impossible, she barely speaks English yet…”

On the return trip, we stayed closer to the east side of the fjord, which gave us a detailed view of the marks left by glacial erosion on the sheer eastern cliffs. Our guide even let me take drive the boat for 20 minutes halfway through the journey, pushing the speed up to about 70 km/h. It was quite a thrill!

Leaving the Arctic

We returned the keys to the hamlet office around 4pm and headed to the airport to catch our flight to Ottawa, connecting through Iqaluit.

Our original booking to leave the Arctic was: Pangnirtung → Iqaluit → Kuujjuaq (another Inuit village in Northern Quebec) → Montreal. However, Canadian North unexpectedly suspended the Kuujjuaq to Montreal flight in early August, so we were rebooked on flight 5T 118, the direct service from Iqaluit to Ottawa. It was the final leg of the “Tundra Express” we had taken to get up north.

On the flight back to Ottawa from Iqaluit, we sat next to an elderly gentleman who had worked as a mechanical engineer for Canadian North Airlines his entire career. He had visited every single Inuit community in Nunavut, and he shared many of his observations and amusing anecdotes with us. He also helped explain a strange phenomenon we had noticed in both Pond Inlet and Pangnirtung: why did most houses have a staircase leading directly into the back wall? What were these stairs for?

The staircases are for people to connect hoses of water trucks and sewage trucks. Only after he mentioned it did we look back at our photos and noticed that, sure enough, there are two pipe connections right on the wall above each staircase. It turns out that most of Nunavut still does not have underground pipes except a few buildings in the capital. Water and sewage trucks must regularly connect hoses to each home to refill fresh water tanks and pump out wastewater.

Bonus: Ottawa

It’s quite surprising that the only flight route from Iqaluit to the southern provinces is Ottawa. There are no direct flights to Toronto or Montreal. I spent an extra day in Ottawa since I hadn’t been here before. The city center is quite compact, and tastefully set against hills and water.

The Canadian Museum of Nature is also really good. The bowhead whale cranium I mentioned earlier is part of the Arctic section of this museum’s exhibition.

I also took the opportunity to satisfy my craving for some wontons and noodles in the city.

Conclusion

This perfectly concludes the journey to Baffin Island! For those interested in my previous posts, you can find them here:

I will be writing up the Greenland parts soon. Get ready to savor it!